Deforestation in Southeast Asia

BY OLIVIA LAIASIA | 7 MAR 2022

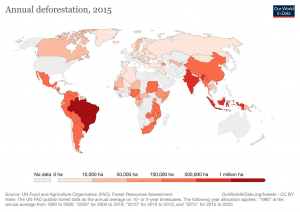

Forests cover just over 30% of the global land area, yet they harbour a vast majority of the world’s wildlife species – including 80% of the world’s amphibians, 75% of birds, and 68% of mammals. But since 1990, over 420 million hectares of forest have been lost as a result of human activity, largely due to deforestation and land clearing for agricultural purposes and logging. Southeast Asia has one of the highest rates of deforestation in the world to support the region’s agricultural and food production, as well as other raw material industries. We discuss what was the major cause of deforestation in Southeast Asia and look ahead to the future.

Southeast Asia, including Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam, and Thailand, is home to nearly 15% of the world’s tropical forests, which makes it all the more attractive as a deforestation hotspot. The region has one of the highest rates of deforestation, losing at least 1.2% of its forests annually, which is comparable only to Latin America where deforestation rates in the Amazon account for one-third of global tropical deforestation.

Deforestation in Indonesia is particularly rampant compared to its Southeast Asian neighbours. Figures from 2019 show that Indonesia alone was responsible for nearly 14% of global tropical deforestation, behind Brazil, North and South America combined, and all of Africa. Between 2001 and 2019, researchers calculated that Southeast Asia had lost 610,000 square kilometres (235,500 square miles) of forest – an area larger than Thailand, 31% of which occurred in mountainous regions where highland forest has been converted to cropland and plantation in less than two decades. Borneo alone, the world’s third-largest island shared between Malaysia, Indonesian Kalimantan and the nation of Brunei, is also projected to lose about 220,000 km sq of forest between 2010 and 2030, approximately 30% of its total land area.

As a result, Southeast Asia has lost more than half of its original forest cover, causing what some experts argue to be one of the most severe biodiversity loss crises. They warn over 40% of the region’s biodiversity will be extinct or completely disappear by 2100 should current deforestation activity continue. What’s more, since tropical forests are some of the world’s most important natural carbon sinks – meaning that they help absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store it – the loss of forest contributes about 10% of human-made greenhouse gas emissions every year, exacerbating the effects of climate change.

Elsewhere in the mountain forest range in north Laos, northeast Myanmar, and east Sumatra and Kalimantan in Indonesia, major forest loss there has been recorded. Clearing forests in these areas where rivers originate “can increase the risk of catastrophic landslides and flooding in lower areas”, not to mention “exacerbates soil erosion and runoff, causing rivers to clog with silt and agricultural pollutants, reducing downstream water quality and availability”.

While governments in the region have adopted measures to limit deforestation, implementations and regulations have proven to be ineffective. Some of Southeast Asia’s intact forests and protected areas have already been degraded and converted for food or logging purposes, likely causing irreversible damage.

You might also like: 10 Deforestation Facts You Should Know About

What was the Major Cause of Deforestation in Southeast Asia?

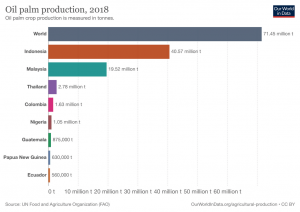

Palm Oil Production

Land use to grow palm has more than quadrupled since 1980, with global production soaring up to 72 million tonnes of oil palm in 2018. The cause behind the surge is the exponential popularity of palm oil in supermarket products, in which the ingredient is used in everything from food products such as biscuits and confectionery to cleaning items like detergents and soaps.

Today, 84% of global palm oil production occurs in Indonesia and Malaysia, accounting for 57% and 27% respectively, making palm oil the major cause of deforestation in Southeast Asia. Thailand is another producer of palm oil in Southeast Asia, where the region’s climate conditions around the equator are ideal and optimal for palm oil production.

In Indonesia, the country has reportedly lost nearly 10 million hectares of primary forest in the past two decades, and a 75% decrease of forest cover from 2019 – its lowest rate since record-keeping began in 1990. A 2019 study identified palm oil plantations to be responsible for 23% (the single largest proportion) of the deforestation in Indonesia between 2001 and 2016. What’s more, over 3 million hectares of the forest estate in 2019 were allocated to palm oil production, which was in strict violation of national forestry law.

Palm tree plantations have a life-cycle of 28-30 years. When trees grow up to a height of over 12 metres, they become uneconomical to harvest the fruits from which the oil is derived. They are then cut and replaced by new trees. It is estimated that up to 300 football fields are cleared globally every hour to make room for palm plantations.

While some studies suggest that palm oil has played a very small role in forest loss while others have argued that palm oil is responsible for around 2% of global tree loss, the ongoing land conversion and deforestation practices for palm oil undoubtedly create a number of impacts on the forest environment, including its ability to absorb carbon dioxide and protection for plant and animal species.

Logging and Croplands

Palm oil production may be on the rise, but logging activities for wood, paper and pulp, as well as timber plantations, have been persistent contributors to deforestation in Southeast Asia, with the biggest danger stemming from illegal logging. Between 1991 and 2014, illegal logging provided 219 million cubic metres of timber in Indonesia, and made up 80% of timber exports in the 2000s, costing the nation over $4 billion in annual revenue.

Land conversion into croplands and pastures also remains to be one of the drivers of deforestation in the region. Smallholder farmers, who own an average of 2.5 hectares of land in Indonesia, often compete with large and organised plantations, prioritising “profitability over environmental stewardship” in the process.

Small-scale agriculture relies on slash-and-burn techniques to quickly prepare land for cultivation is widely practised in Borneo. As the name suggests, the farming method cuts down trees and vegetation, which are then dried and burnt. The resulting layer of ash provides the newly-cleared land with a nutrient-rich layer to help fertilise crops. But after a few years, the nutrients are used up with the land degraded, forcing farmers to move on to a new plot of land and restart the process all over again, degrading even more forest along the way. According to NASA researchers, accelerated slash-and-burn contributed to the largest single-year global increase in carbon emissions in two millennia, which pushed Indonesia upwards into the world’s fourth-largest source of carbon emissions.

Additionally, the slash-and-burn method significantly increases the risk of wildfire, which is already evident in Indonesia. The 2019 fires were especially damaging; releasing 708 million tonnes of carbon dioxide, which is twice the amount released by wildfires in the Amazon in the same year due to the burning of peatlands.

Impacts on Biodiversity

Deforestation in Southeast Asia for palm oil production, logging and agriculture purposes continues to destroy key habitats of already critically endangered species like the orangutan, the Javan rhino, and the Sumatran tiger.

The latter of which has already suffered severe loss from wildlife poaching and trading. With the growing loss of their forest habitats, there are fewer than 400 Sumatran tigers remaining in the wild. Deforestation is also the biggest threat to the orangutan, one of the world’s most unique arboreal mammals and found only in parts of Borneo and Sumatra. Not only is the species losing its habitats, but increased wildfires from slash and burn have reduced the availability of fruit, forcing many orangutans to resort to eating tree bark, which is also declining due to both logging and large-scale farming. Smoke from the fires also weakens orangutans’ immune system and damages their DNA.

Aside from habitat loss, tree and forest loss also increases the impact of biodiversity resilience to climate change, where forest species that may have otherwise been able to shift their distributions in response to warming will have less space to do so.

The Future of Deforestation in Southeast Asia

Despite such wide scale environmental impacts, countries in Southeast Asia, especially Indonesia, continue many of their environmental rollbacks, working in opposition to the Paris Agreement climate goals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Though some studies are optimistic in spite of current actions and trajectories, noting that there have been significant indications of favourable landscape changes leading to afforestation and forest regrowth in Southeast Asia. The 2019 study estimated that under the worst case scenario, forests in the region could be lost by 5.2 million hectares by 2050, but in the best case scenario, the region is projected to gain 19.6 million hectares of forests by “inclusive development and respect for perceived environmental boundaries, as well as high investment in human capital, education and awareness”.

At the recent COP26 climate conference, more than 100 countries including Indonesia took a pledge to stop and reverse deforestation by 2030, though the country seemed to immediately backtracked as Siti Nurbaya Bakar, the Indonesian minister of environment and forestry, took to Twitter and stated that Indonesia’s commitment to ending deforestation would not come at the expense of its economic development. For now, it remains to be seen how far and stringent nations are willing to combat deforestation.

Featured image by: Wikimedia Commons