The Sordid History of Forest Service Fire Data

by Randal OToole 09/27/2018

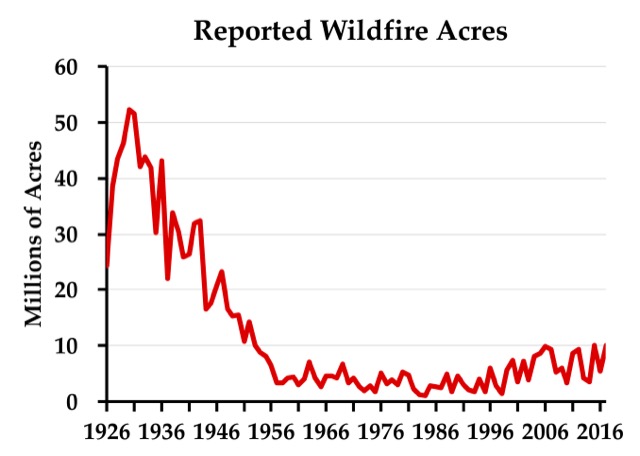

The latest wildfire situation report indicates that about 7.3 million acres have burned to date this year. That’s about 1.2 million acres less than this same date last year, but about 1.5 million acres more than the ten-year average and a lot more than the average in the 1950s and 1960s, which was about 3.9 million acres a year. Some people use the data behind this chart to argue against anthropogenic climate change. The problem is that the data before about 1955 are a lie. Click image to go to the source data.

Some people use the data behind this chart to argue against anthropogenic climate change. The problem is that the data before about 1955 are a lie. Click image to go to the source data.

While some blame the increase in acres burned on human-caused climate change, skeptics of anthropogenic warming have pointed out that, according to the official records, far more acres burned in the 1930s — close to 40 million acres a year — than in any recent decade. The 1930s were indeed a decade of unusually bad droughts that can’t be blamed on anthropogenic climate change.

While the Antiplanner isn’t persuaded that recent fires are evidence of human-caused global warming, reports of acres burned from before about 1955 are not evidence of the opposite for a simple reason: the Forest Service lied. While the Antiplanner has alluded to this before, it’s important to tell the full story so that skeptics of climate change don’t reduce their credibility by using erroneous data.

The story begins in 1908, when Congress passed the Forest Fires Emergency Funds Act, authorizing the Forest Service to use whatever funds were available from any part of its budget to put out wildfires, with the promise that Congress would reimburse those funds. As far as I know, this is the only time any democratically elected government has given a blank check to any government agency; even in wartime, the Defense Department has to live within a budget set by Congress.

This law was tested just two years later with the Big Burn of 1910, which killed 87 people as it burned 3 million acres in the northern Rocky Mountains. Congress reimbursed the funds the Forest Service spent trying (with little success) to put out the fires, but — more important — a whole generation of Forest Service leaders learned from this fire that all forest fires were bad.

In 1924, Congress passed the Clarke-McNary Act, which allowed the Forest Service with (i.e., provide funds to) “appropriate officials of the various states or other suitable agencies” in developing “systems of forest fire prevention and suppression.” The Forest Service used its financial muscle to encourage states to form fire protection districts.

This led to a conflict over the science of fire that is well documented in a 1962 book titled Fire and Water: Scientific Heresy in the Forest Service. Owners of southern pine forests believed that they needed to burn the underbrush in their forests every few years or the brush would build up, creating the fuels for uncontrollable wildfires. But the mulish Forest Service insisted that all fires were bad, so it refused to fund fire protection districts in any state that allowed prescribed burning.

The Forest Service’s stubborn attitude may have come about because most national forests were in the West, where fuel build-up was slower and in many forests didn’t lead to serious wildfire problems. But it was also a public relations problem: after convincing Congress that fire was so threatening that it deserved a blank check, the Forest Service didn’t want to dilute the message by setting fires itself.

When a state refused to ban prescribed fire, the Forest Service responded by counting all fires in that state, prescribed or wild, as wildfires. Many southern landowners believed they needed to burn their forests every four or five years, so perhaps 20 percent of forests would be burned each year, compared with less than 1 percent of forests burned through actual wildfires. Thus, counting the prescribed fires greatly inflated the total number of acres burned.

The Forest Service reluctantly and with little publicity began to reverse its anti-prescribed-fire policy in the late 1930s. After the war, the agency publicly agreed to provide fire funding to states that allowed prescribed burning. As southern states joined the cooperative program one by one, the Forest Service stopped counting prescribed burns in those states as wildfires. This explains the steady decline in acres burned from about 1946 to 1956.

There were some big fires in the West in the 1930s that were not prescribed fires. I’m pretty sure that if someone made a chart like the one shown above for just the eleven contiguous western states, it would still show a lot more acres burned in real wildfires in the 1930s than any decade since — though not by as big a margin as when southern prescribed fires are counted. The above chart should not be used to show that fires were worse in the 1930s than today, however, because it is based on a lie derived from the Forest Service’s long refusal to accept the science behind prescribed burning.

This piece first appeared on The Antiplanner.

Randal O’Toole (rot@ti.org) is a senior fellow with the Cato Institute and author of the new book, Romance of the Rails: Why the Passenger Trains We Love Are Not the Transportation We Need, which will be released by the Cato Institute on October 10.

Source Link: http://www.newgeography.com/content/006096-the-sordid-history-forest-service-fire-data