Fires and haze return to Indonesia as peat protection bid falls short

by Aseanty Pahlevi, Hans Nicholas Jong, Zamzami on 29 August 2018

JAKARTA/PONTIANAK/PEKANBARU — Like their compatriots across Indonesia, a group of residents in the Bornean city of Pontianak celebrated the country’s Independence Day on Aug. 17 with a flag-raising ceremony.

But for them, the simple act of hoisting the Red-and-White was a physically taxing endeavor, thanks to the toxic haze billowing from a smoldering plot of peatland nearby. The sound of wood crackling in the fire could be heard as the participants, their surgical masks doing nothing to keep the smoke out of their eyes, stood through the ceremony. When it was over, they returned to what they were doing: working to put out the pockets of fire flaring up from the mulch-rich peat soil.

Beni Sulastiyo is one of the leaders of this group of residents of Pontianak, the capital of the province of West Kalimantan, who have banded together as volunteer firefighters. He says they see the fire problem as something that the whole community, and not just the government, needs to address.

“This should be a shared responsibility for everyone. As members of the community, we’re on the same page in helping the government,” he says.

Ateng Tanjaya is nearly 70, and has worked as a volunteer firefighter in Pontianak for more than 40 years. The work is often thankless, he says, and the hardships legion: lack of hoses and fire equipment, shortage of water, and scant funding and logistical support.

For these volunteers, the fires won’t end any time soon. The dry season is kicking in, and after a relatively haze-free 2016 and 2017, conditions this year look ripe for the fires to grow out of control.

Deadly heat

There have been nearly 2,200 fire hot spots recorded across Indonesia between Jan. 1 and Aug. 14, according to the Indonesian Forum for the Environment (Walhi), the country’s leading green NGO. West Kalimantan recorded the highest number of any province, at 779.

At least four people are confirmed to have died in the fires in the province. The latest victim, a 69-year-old farmer in Sintang district, reportedly died while trying to put out a blaze on his land on Aug. 19. Six days earlier, a family of three in Melawi district died in their burning house.

In Pontianak, the haze has sometimes been so thick that visibility is limited to 5 meters (16 feet). Flights into and out of the city’s Supadio International Airport are under constant threat of being cancelled or diverted whenever visibility drops below 1,000 meters (3,300 feet). Elsewhere across the province, schools were ordered shut on Aug. 20 when the haze worsened.

Satellite imagery from the Global Forest Watch platform shows smoke plumes in the most affected areas, including Pontianak and Ketapang district.

Air quality in Pontianak has been declining in recent weeks, according to data from the national weather agency, the BMKG, uploaded to the global monitoring platform IQAIR Air Visual. This has been marked by an increase in the concentration of tiny carcinogenic particles known as PM2.5 in the air.

These particles are small enough to enter the bloodstream; long-term exposure to them can cause acute respiratory infections and cardiovascular disease.

PM2.5 concentrations crossed into dangerous territory on Aug. 19 and 23, when the average daily levels registered at 73.5 and 79 micrograms per cubic meter, respectively — triple the World Health Organization’s guideline level of 25 micrograms per cubic meter in a 24-hour period.

‘Shoot on sight’

It’s a similar story across the Karimata Strait from Borneo, on the island of Sumatra. Norton Marbun, a resident of Rantau Benuang village in Riau province, says the fires there began on Aug. 14, razing the villagers’ oil palm farms.

He was out in the fields helping fight the flames, he says, and almost didn’t notice the fire closing in on his house, where his wife and children were sheltering. He rushed back to find the house, which he’d just finished building three months earlier after 11 years of saving up, filled with smoke. His wife didn’t want to leave — the house was all they had, she said — and Norton says he had to drag her and the kids out as the flames bore down.

They were barely out when a gas canister exploded inside the house. “If I’d been even 10 minutes late, maybe my family would have been skeletons inside the house,” Norton says.

They lost everything with their house, including two motorcycles. The family has since moved to a neighboring village. But even there they can’t escape from the haze.

“Now my children are having difficulty breathing due to the haze,” Norton says.

As growing forest and peat fires fan the haze across Riau, the military has been roped into the effort to fight the fires. A local military commander says nearly all the fires are set deliberately, and has issued a shoot-on-sight order for anyone caught doing so. (It’s not clear how this would be justified; Indonesian law has clear statutes proscribing extrajudicial shootings by law enforcement.)

Policy failure?

Forest and peat fires are an annual occurrence in Indonesia. In 2015, the country suffered one of its worst burning seasons in years, with more than 20,000 square kilometers (7,700 square miles) of land razed — an area four times the size of Grand Canyon National Park. The resultant haze sickened hundreds of thousands people in Indonesia and spread into Malaysia and Singapore.

On the heels of that disaster, President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo announced a series of measures aimed at preventing future fires. These include an ambitious plan to restore 24,000 square kilometers (9,300 square miles) of degraded peatland and imposing a moratorium on peat clearance.

The policies seem to have paid off, with a significant reduction in the number of hotspots in 2016 and 2017. Last year, officials recorded zero days with haze resulting from forest fires.

The government has repeatedly cited those figures as proof that its policies are working. But some of this year’s fires have flared up in regions prioritized by the government for peat restoration, including West Kalimantan and Riau.

Walhi, the environmental watchdog, says it has detected hotspots within peat hydrological units, the areas of peatland bordered by rivers or other bodies of water.

“The fact that this year the number of hotspots is very high in West Kalimantan shows that efforts to improve peat governance in the province have failed,” Anton P. Widjaya, director of Walhi’s West Kalimantan chapter, said at a recent press conference in Jakarta.

He said Walhi had compared the number of hotspots in peat areas before and after the government launched its program under the auspices of the Peatland Restoration Agency (BRG), and found no improvement.

“It turned out the number of hotspots didn’t differ that much,” Anton said. “So the work that the BRG has done on the ground hasn’t had a significant impact over the short term. The fact is that fires are still happening in these priority areas during the dry season.”

Riko Kurniawan, the director of Walhi’s Riau chapter, said the return of the fires in the province this year showed the government’s programs had been boosted in the previous two years by a less-severe dry season.

“Sure, there was no haze in Riau in 2016 and 2017, but that’s because the dry seasons those years were wetter, and because the government did its best to extinguish fires,” Riko said at the press conference. “But what about peat restoration and protection? As far as we’re concerned, that’s stagnant.”

Rewetting peat

BRG head Nazir Foead says the government’s peat restoration efforts might not be enough to prevent this year’s fires simply because of the sheer size of peat areas that have been degraded and are thus prone to burning again.

He cites the case of a village in Riau that was included in the peat restoration program last year. The village is surrounded by dozens of square kilometers of peatland that have to be rewetted to prevent fires from breaking out. To this end, the villagers blocked the canals that were previously dug to drain the land in preparation for planting.

But the work only took place two months before the onset of the dry season, and not all of the canals could be blocked in time.

“And indeed, fires happened this year on the edge of the village that hadn’t been restored yet,” Nazir says.

Even after drainage canals have been blocked, it can take years of rains before a peat area is restored to its original wet, sponge-like condition.

“If all the canals have been blocked, does that ensure there’ll be no more fire? Not really,” Nazir says. “Because the peatland has been dried out for so long, and so when the canals are blocked, the peatland isn’t immediately rewetted.”

In addition to working with villages that are prone to fires, the peat restoration program also requires companies to restore degraded peatland inside their concessions. The Ministry of Environment and Forestry has approved the peat restoration plans of 45 timber plantation companies and 107 oil palm and rubber plantation firms, according to Karliansyah, the ministry official in charge of environmental damage mitigation.

The ministry is still waiting for 80 more oil palm and rubber plantation companies and more than 30 timber plantation companies to submit and revise their restoration plans, he added.

“I guarantee that the 45 timber companies and the 107 plantation companies have done [peat restoration],” Karliansyah said. “But outside those companies, there might still be degraded peatland. If the weather is dry and there’s a small fire, then the fire could spread.”

Trading blame

The ministry’s fire mitigation chief, Raffles B. Pandjaitan, says this year’s increase in hotspots coincides with the start of the land-clearing season in West Kalimantan, where local farmers practice a traditional method of slash-and-burn called gawai serentak.

He says the farmers take advantage of the dry season, which peaks in August and September, to burn their land, after which they begin planting.

“It’s during this slash-and-burn season that the risk of fires is at its greatest,” Raffles said in a press release. “If we don’t keep the slash-and-burn practice under control, the fires will spread to other, bigger plantations.”

Walhi has refuted the government’s claim, saying many of the hotspots it has detected are in the concessions of large companies, not the farms of smallholders. The group says there have been 765 fire spots in corporate concessions so far this year.

Walhi executive director Nur Hidayati says it’s likely the government is blaming smallholders for this year’s fires because its own firefighting efforts so far have been focused on areas close to these villages.

“But [fires on] companies’ concessions that are far from villages are being ignored,” she told Mongabay in Jakarta recently.

Walhi spokeswoman Khalisah Khalid says that while some indigenous communities continue to practice slash-and-burn clearing, they do so in a way that keeps the fire contained. This keeps the fires from spreading outside the communities’ land and damaging the environment, according to a 2016 Walhi study on how traditional communities manage peatlands.

“Indigenous peoples have always been blamed for causing forest and peat fires,” Khalisah says. “But as this study shows, there are 20 steps that the Dayak indigenous tribe have to go through when they want to cultivate peatland.”

She also notes that a 2009 law that allows smallholders to clear land by burning up to 2 hectares (5 acres) — a stipulation aimed at preserving traditional methods of land clearing. By blaming traditional farmers for this year’s fires, the government has failed to understand the importance of local wisdoms about farming on peat, Khalisah says.

Walhi attributes the outbreak of fires this season on companies that went unpunished for previous fires and were thus emboldened to continue to the practice.

The government itself is also to blame for preventing the fires. That, at least, is the judgment of a court in Central Kalimantan province, which recently ruled in favor of a citizen lawsuit calling on the president and various ministers and other senior officials to be held accountable for the 2015 fires. In their suit, the plaintiffs argued that the government failed in its duty of protecting residents of Central Kalimantan from the impact of the fires.

The respondents in the lawsuit include the president; the ministers of environment, agriculture, land, and health; and the governor and provincial legislature of Central Kalimantan.

In its ruling, the high court in Palangka Raya, the provincial capital, ordered the respondents to pass regulation to mitigate land and forest fires

The government, however, is appealing the case to the Supreme Court, to the dismay of activists.

“I think there’s no need for the president to be defensive and file an appeal,” Walhi water and ecosystem campaigner Wahyu A. Pradana told local media. “What the president should do is obey all the orders in the ruling, because they’re for the sake of the people.”

Walhi has also called on the authorities to take action against companies with fires on their concessions, instead of going after local farmers. The environment ministry in mid-August sealed off concessions held by five companies in Kubu Raya district, West Kalimantan. It did not identify the companies by name.

“The government is very serious in handling land and forest fires,” Rasio Ridho Sani, the ministry’s head of law enforcement, said in a press release. “This move is to support our law enforcement effort so that there’s a deterrent effect. We will keep monitoring other burned locations using satellite and drone.”

Banner image: A group of locals in West Kalimantan participates in a flag-raising ceremony amid toxic haze from nearby peat fires. Image by Aseanty Pahlevi/Mongabay Indonesia.

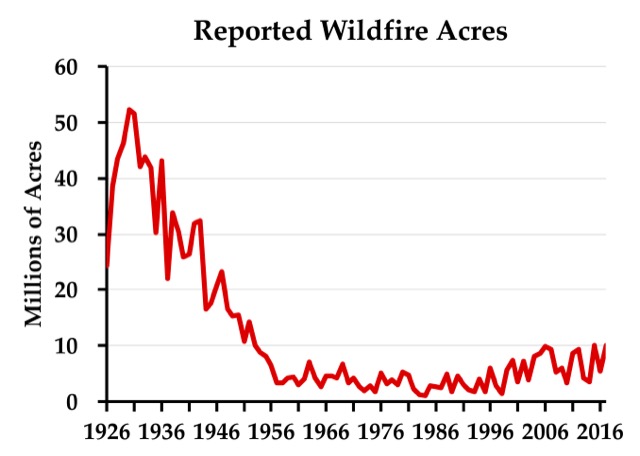

Some people use the data behind this chart to argue against anthropogenic climate change. The problem is that the data before about 1955 are a lie. Click image to go to the source data.

Some people use the data behind this chart to argue against anthropogenic climate change. The problem is that the data before about 1955 are a lie. Click image to go to the source data.